MKULTRA's Terminal Experiments

5248-word essay on an especially covered-up part of Project MKULTRA, the CIA's mind-control program which existed from 1953 to 1973.

I was going to include this essay in my in-progress essay collection Reasons to Live, but recently I decided the collection will have personal essays only. I can put this essay and other non-personal essays (one on Neolithic religion, one on suppressed physics, my Deep State one) in a separate collection titled Dystopia.

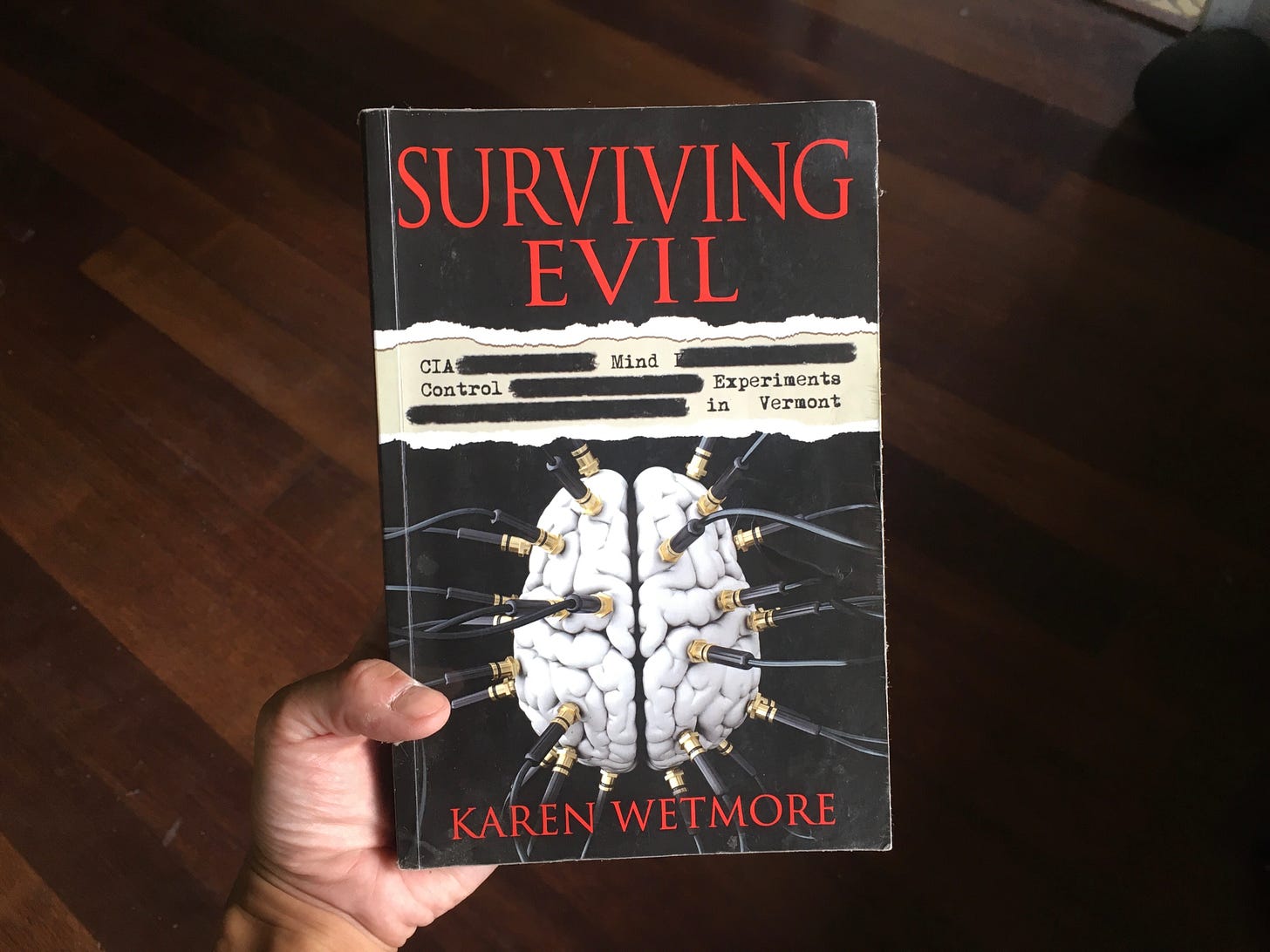

This essay focuses on Surviving Evil (2014), in which Karen Wetmore writes about surviving “terminal experiments” done by the CIA’s Project MKULTRA at Vermont State Hospital, a mental hospital. In a terminal experiment, the person being experimented on is expected to die as a result of the experiment.

MKULTRA’s Terminal Experiments

Karen Wetmore was born in 1952, a year before the start of Project MKULTRA, the CIA’s secret mind-control program. She grew up in a small town in rural Vermont. In the mid-or-late fifties, she was molested by a local man; she had no conscious memory of this and did not realize it until she was in her forties. She had other childhood traumas, which she also repressed, and when she was eleven she began to have suicidal thoughts.

In 1965, when Karen was thirteen, she was found wandering the halls at school confused and disoriented. When the family doctor arrived, she told him that if he sent her home she would kill her mom or herself. Her dad and brother took her to Mary Fletcher hospital, where she was given Sodium Amytal and the phenothiazines Thorazine and Stelazine. She was allergic to phenothiazines. She slashed her wrist with a glass urine specimen bottle. A doctor told her the only reason she wasn’t being sent to Vermont State Hospital—a mental institution—was because no one had told her suicide attempts were “not tolerated.”

Days later, in a psychological test, she was asked, “What does two heads are better than one mean?” Her response—“If you are crazy in one head, you still have one more head to save”—elicited “a dramatic reaction from the doctors,” she wrote in Surviving Evil (2014). On October 21, 1965, the adverse drug reactions had gotten so severe that a consulting doctor was brought in. According to the hospital’s records, the doctor diagnosed Karen with an allergic reaction to phenothiazines and advised they be stopped, but the drugs were not stopped and soon she began screaming uncontrollably. She was told that if she didn’t stop screaming, she would be sent to Vermont State Hospital.

“No matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t stop screaming,” she wrote. And so on October 24, after thirty days in Mary Fletcher hospital, she was transferred by ambulance to Vermont State Hospital (VSH) despite the pleas of her mom on the phone with a doctor; it was the only time Karen saw her dad, who was in the ambulance with her, cry.

Karen’s VSH admission record said she’d “attempted suicide severing the palmaris longus tendon in left wrist” and that her face and body were covered in rashes and bruises. She was put in a straightjacket and injected with Trilafon and Compazine, causing “spasms in the corner of her mouth and the side of her face” and “apparently in her diaphragm causing a loud moan,” according to the record, which described Karen as “very frightened.” She was placed in Weeks 3, the locked adult women’s ward.

In December, VSH doctors disallowed Karen to return to school and kept her on the adult ward even though VSH had a children’s ward. She was prescribed Mellaril, a phenothiazine. She was given a test called Psychological Assessment System. “PAS objectives are to control, exploit, or neutralize,” according to a 1963 CIA document quoted in Surviving Evil. “These objectives are innately anti-ethical rather than therapeutic in their intent.” The results were sent to CIA headquarters. Karen’s parents told VSH doctors about her love for horses, close relationship with her grandfather, “unusually intense reaction” to JFK’s assassination, and that she ran away when she was five—information they thought would help the doctors help Karen, who was labeled “schizophrenic.”

In March 1966, she was released (“Now I was the crazy girl”), in early 1967 she returned to VSH for six weeks, and in 1968 she met a man named Phil Cram and they decided to marry, but he died in a car accident. Karen’s parents urged her to begin taking Mellaril again. She developed “severe vomiting” and “a strange black fur” on her tongue.

At Rutland hospital, her reaction to Mellaril was diagnosed as hepatitis and she was prescribed Paraldehyde and other drugs, leading to panic attacks and uncontrollable screaming. Against the protests of the nursing staff and her parents, she was sent back to Vermont State Hospital, which had been called Vermont State Asylum for the Insane until 1898, when it was renamed Vermont State Hospital for the Insane. (A sentence from the 1898 biennial report by the hospital’s then-superintendent gives us an idea of what the word insane meant in 1898: “Notwithstanding the general belief in the incurability of insanity, facts incontestably prove that the majority of insane do recover if proper treatment is early instituted.”)

It was October 12, 1970, and Karen was eighteen. At VSH, according to the record, she threw chairs and was transferred on October 19 to 1A—“the most dreaded ward in the hospital,” where many women “considered to be hopeless” had been for years and were probably, Karen theorized, “the target VSH population for the use of experimental drugs”—where she was put in seclusion. “I woke up on the floor, naked, with my arms secured behind my back in leather wristlets. The gnawing, searing pain in my arms, neck and shoulders was impossible to relieve.” She “heard frightening screams and strange shrieks.” She was kept in these conditions, according to hospital records, until October 23, when Dr. Otto Havas moved her to Weeks 3.

At Weeks 3, Havas told her she would be transferred to 10B. In response, she “ran wildly down the hall” and smashed her head through a door’s glass window. After three days of seclusion on 1A, she was moved to 10B for eight days, then back to seclusion on 1A. She went back and forth between 1A and 10B—a ward of which no records exist except “scattered notations by Havas later in the record.” On December 12, Havas began writing orders for “vaginal suppositories,” of which Karen would receive twelve over five months—with “no medical reason noted anywhere in the records”—while “tied to a bed in a straightjacket.” Decades later, her research would lead her to suspect she’d been sexually assaulted by one or more doctors.

Beginning on December 30, Karen was kept, the record showed, in seclusion for up to fourteen days at a time, with no food or water for up to three days at a time. “When in seclusion, I was often kept naked. My arms were secured behind my back day and night.” There was no mattress, blanket, or toilet. When not straightjacketed (“Each time the wristlets were removed, I was placed in a straightjacket”), she smashed her head into the door and walls, a behavior she later learned was “common among people who are kept in extended periods of isolation.” She was prescribed up to eight different drugs at a time and subjected to “two complete drug washouts” and “regular enemas.” She received placebos that were probably actually active experimental drugs. Her mom was repeatedly told that her daughter refused to see her.

In April 1971, Karen received eight electric shock treatments (ECTs) of thirty to thirty-five shocks in forty seconds, though the “standard number of shocks given by medical professionals was one shock maintained for a fraction of a second.” Twice, the ECT didn’t produce a seizure and the process was repeated. That same month, Judge Henry Black signed the visitor log in VSH North office and tried to see Karen. VSH refused to allow him to see Karen. The same day, Karen’s mom also was trying to see Karen and Judge Black introduced himself and was “visibly angry” but left without seeing Karen or following up—an example of one of several individuals who suspected something was amiss, investigated to some degree, and stopped.

On June 18, Karen underwent four ECTs in one day by Havas and that night was treated by a different doctor for eye and facial injuries. In Surviving Evil, she wrote:

ECT is known to cause amnesia and I believe that Havas conducted the treatments not only as part of the experiment, but also to ensure that my memories of 1A were gone. For the most part, he was successful.

On June 21, after eight months of almost uninterrupted seclusion in 1A, Karen left VHS. In the car, on Interstate 89, looking out the window at a clear blue sky, she cried. “I was overwhelmed by the knowledge that I had made it out of that terrible place alive.” She was brought to a Degoesbriand hospital, where she had “few memories of the almost three weeks on the neurology unit.” She was, again, prescribed Thorazine and Stelazine despite being allergic. She complained, the record showed, about her treatment at VSH, but when asked for details “couldn’t provide any.”

She received electroencephalograms. “During one, I was placed in a strange room with walls on all four sides that looked like plastic. Suddenly as I lay hooked up to EEG leads, a man rushed into the room and broke a glass bottle on the floor. I reacted by crying.” The record stated: “The patient was purposefully upset by the breaking of the bottle.” In a test on June 28, she was given phenobarbital, an EEG, and 1800 milligrams of Metrazol, a drug used, according to CIA documents, on POWs in Soviet gulags and which, Karen wrote, causes “excruciating physical and psychological pain, so severe that a POW is said to, ‘Say or do anything to avoid another dose of the drug.’” In The C.I.A. Doctors (2006), Canadian psychiatrist Colin Ross quoted a CIA document which stated:

Metrazol, which has been very useful in shock therapy, is no longer popular because, for one thing it produces feelings of overwhelming terror and doom prior to the convulsion. But terror, anxiety, worry would be valuable for many purposes from our point of view.

Karen told nurses she heard men in her head. She recognized that she was hallucinating and she accused the doctors of giving her hallucination-causing drugs. “Metrazol was used in MKULTRA to produce amnesia and as a way to negate the effects of LSD,” she wrote in Surviving Evil, in which she theorized that she was dosed with LSD while at VSH.

The night of the Metrazol test, Karen tried to set herself on fire in a bathroom. “I can only imagine that when I was transferred from the brutal conditions in VSH to the Burlington hospitals, that I must have believed that I was finally safe. I suspect that after the administration of the Metrazol, I understood that I was not safe in the new hospital.” She was moved to a psychiatric unit called Baird 6. “On each page of my Baird 6 medical records my name is noted as ‘Skippy.’ The staff called me by this name, as did the doctors. Beginning with my admission to the neurology unit on June 21, 1971 and throughout the four months I spent on Baird 6, it appears that I was no longer Karen.”

On Baird 6, though no cause for pain was recorded, she was given painkillers—probably, she discovered decades later, because she’d been surgically implanted behind her ear. She had “unexplained episodes” where she “ran head first into walls, doors or people.” The record showed there was “a concerted effort by the psychiatrists” to have her accept she was “schizophrenic” and that she fought the diagnosis. She attempted suicide repeatedly. In July and August she seemed to have been secretly given LSD. In October, after a suicide attempt, she was sent back to VSH. “My records note that I said numerous times over the four months I was on Baird 6 that I would rather be dead than ever go back to VSH,” she wrote in Surviving Evil.

At Vermont State Hospital, on October 29, she was placed on Weeks 3. Since Baird 6, she’d begun sometimes finding herself having escaped the hospital, and this continued at VSH. Strangely, she was, despite being under close observation, always successful, making it usually to the interstate before being returned to the hospital by police officers. “I would have been very aware of the fact that escaping VSH brought consequences, yet I escaped time after time for reasons I cannot explain. The records note the escapes but show nothing that might explain the reasons why I might have run.”

She seemed to be monitored during these experiments, which seemed to exploit information her parents told doctors when she was thirteen. “I believe that my escapes were not only part of the experiment but that they involved the use of a triggered response mechanism set up in me by hypnosis and implants,” wrote Karen, who, besides the ear-implant, would also later discover a mouth implant. (In 2009, the mysterious object would fall out of her mouth. Her doctor would find a surgical slit on the inside of her right cheek, another doctor would confirm the slit, a third doctor would say the object couldn’t have been from a dental procedure, and a fourth doctor would examine it under a microscope and conclude it seemed to be rock and didn’t seem to contain any electronic parts.)

On June 19, 1972, the day CIA director Richard Helms ordered the destruction of MKULTRA files, Karen was discharged from Vermont State Hospital. At her parents’ house, she “tried to begin a normal life” but inexplicably hitchhiked back to VHS. “I don’t remember what happened, if anything, to cause me to escape again only days after,” she wrote. The Vermont State police bought her cigarettes and sodas and listened to her “hatred of VSH”—she wasn’t able to provide any specifics—then drove her back to VSH, where she was placed on the locked ward, now called 2A. This time she wasn’t restrained or secluded. During her four months on Baird 6 and nine months on Weeks 3, she’d been called Skippy, but now she was Karen again.

Two months later, in September, she left Vermont State Hospital for the final time.

For the next twenty-five years, from ages twenty to forty-five, Karen lived unaware of most of what happened to her at VSH and some of what happened to her at other Vermont hospitals, like the Metrazol test. From when she left VSH at the end of 1972 until 1997, when she began to learn about her history, odd and frightening things continued to happen to her.

In 1976 or 1977—the year of the Senate’s MKULTRA hearing, in which Ted Kennedy stated, “Perhaps most disturbing of all was the fact that the extent of experimentation on human subjects was unknown. The records of all these activities were destroyed in January 1973.”—a woman led Karen, at the Phipps Clinic, into a room where around a dozen men were seated in chairs. She sat in a chair. “I recall looking around the circle of men in suits and ties and my memory ends there,” she wrote. “I have no memory of any question I was asked or my responses or how long I was in the room.”

In 1981, Karen was diagnosed with multiple personality disorder. That year, in Copley Hospital, nurses brought in a man in a suit-and-tie to talk to her. “He described how a person living in a one-dimensional world would never be able to comprehend what it was like to live in a three-dimensional world. He asked me if I understood the point he was trying to make and I said that yes, I understood. I don’t remember if we talked about anything else and I don’t remember him leaving.”

In 1987, she had “a severe allergic reaction to Haldol” and what a doctor called a “psychotic break” in which she seemed to have been dosed with LSD, causing, she felt, a flashback to her Metrazol experience. Analysis of the flashback suggested the CIA had used hypnosis and the childhood information supplied by her parents to be able to command her to pick up and fire a gun and flee the scene and kill herself.

In 1988, she began therapy with Kathy Judge, whom she trusted. Kathy said Karen had been “floridly multiple” for a long time. “During the first few months of therapy I began to dissociate more often and my personalities became more separate,” wrote Karen. For reasons she “cannot recall,” she took out a loan and rented a car and began driving for hours. One day she bought a gun and “began driving aimlessly searching for the place I was supposed to go.” She ended up in a motel, looking at herself in the mirror with the loaded gun against her temple. She called Kathy and unloaded the gun.

In 1994, as part of her productive but often “excruciating” therapy, Karen called Janet, a childhood next-door neighbor she’d “spent a good deal of time with.” Janet had been in her early 20s when Karen was four. “I felt ridiculous asking Janet if anything out of the ordinary or traumatic had ever happened on the land when she was with me,” wrote Karen. Janet revealed that her husband Willy had “sexual relationships with his own daughters.” On another phonecall, Karen directly asked Janet if her husband had sexually molested her. Janet said yes.

Karen talked to more people and learned more forgotten trauma. She learned she saw her dad shoot a cat, accidentally bury it alive, dig it out, and repeatedly fire bullets into it when she was three. She learned she pulled a table onto herself, cutting her mouth, when she was nine months old, and that both she and her mom “became hysterical.” She learned other childhood trauma, including more involving guns. “Kathy said she believed that if the shootings and the molestation had not occurred, the chances of my becoming multiple would have been much less,” she wrote.

In the fall of 1997, at age forty-five, when Karen was “feeling increasingly overwhelmed” by “the intrusion of some other terrible world,” Kathy suggested she write a narrative of her life. This led to Karen requesting her medical records from the State of Vermont. She was flatly refused. She persisted and made more calls and hired a lawyer, who was also refused access to the records. After weeks of work, the lawyer, Alan, succeeded and the records were dropped off at Karen’s apartment. “What would I read about myself in those records? What awful things would they say about me? Would they confirm that I was the monster that I had believed myself to be?”

Her “heart began to pound” as she located “the 1970-1971 seclusion room charts.” She learned about the drugs, electric shock treatments, vaginal suppositories, and months of seclusion. She read letters from her mom pleading with VSH’s superintendent and the Mental Health Commissioner to not treat her harshly. She was horrified by the conditions she’d been kept in and by the fact that she “could not remember a substantial portion” of her life. Seven years later, she would write:

One of the positive emotional effects that came with learning that I had been used in CIA experiments was that, for the first time since I was thirteen years old, I realized that it wasn’t because of something terrible about me. It was because of the terrible things that were done to me. It was a life altering realization.

Kathy and Alan also read the records. It was “quickly determined” Karen had been “experimented on.” She decided to sue the state. “As much as I wanted to name the CIA as a defendant in the suit, I agreed with Alan when he said that to do so would tie me up in the courts for possibly decades.” With the help of Kathy and others, Karen began slowly, over years, to uncover what happened to her and thousands of other mental patients in American hospitals.

She read Schizophrenia: A Review of the Syndrome (1958), The Use of LSD in Psychotherapy (1960), The Vermont Story: Schizophrenic Rehabilitation (1961), The Search for the Manchurian Candidate (1979), Acid Dreams (1985), Empty Beds: A History of Vermont State Hospital (1988), Father, Son, and CIA (1990). She crafted strategically worded Freedom of Information Act requests to multiple governmental organizations.

She contacted elected officials. “When confronted with original source documents, no State or federal official would respond, with the exception of Senator Bernie Sanders. Even Sanders was not willing to go public with the information.” CNN, ABC, NBC, FOX, CBS, and the New York Times weren’t interested.

Her mail was regularly stolen, and the phone company told her her phone had been tapped. Men she didn’t know followed and tried to talk to her. Years later, she’d suspect that one of these men might’ve been protecting her: “I asked Colin Ross for his opinion and he speculated that I might have created a division within the intelligence community.” Men stopped following her in 2011 after (1) Bernie Sanders’ office told her they’d send a Congressional Liaison officer to complain to the CIA about the stalking, and (2) she called the FBI to report that a man she’d identified as an FBI agent had been following her.

Her lawsuit ended in 2002 after her second heart attack, when her doctor said if she continued the trial she could die. But she continued obtaining source documents, deepening her investigation. She read A Mind for Murder: The Education of the Unabomber and the Origins of Modern Terrorism (2004), The C.I.A. Doctors: Human Rights Violations by American Psychiatrists (2006), A Terrible Mistake: The Murder of Frank Olson and the CIA's Secret Cold War Experiments (2009), and other books.

She discovered that the CIA experiments in Vermont seem to have been especially kept secret, more so than other MKULTRA subprojects. She wrote that the “Vermont CIA experiments might very well have remained covered up” if she hadn’t gotten her Vermont State Hospital medical records in 1997, found the name Robert W. Hyde, and learned he was the same Hyde who worked for the CIA, conducting drug and mind control experiments. She wrote:

CIA defenders like to point out that the drug and mind control programs have already been investigated and that nothing new would be learned. I beg to differ. If I have been able to document the massive presence of CIA in Vermont institutions, what might the government with all its resources be able to learn? The lack of interest in an investigation has everything to do with making sure that the CIA activities in Vermont remain covered up.

The Vermont experiments remained secret until November 30, 2008, when the Rutland Herald published a 4683-word front-page article on Karen. Eighteen months earlier, Karen had called the newspaper and met with its editor. The article, titled “Evidence suggests CIA funded experiments at state hospital,” referenced Karen’s medical records and was the first time the public heard anything about CIA experiments in Vermont. Its author, Louis Porter, wrote about the difficulties of researching MKULTRA: “Few of the individuals interviewed for this story were willing to speak on the record; many of the most important potential sources are now deceased.” He referenced a 1994 government report that stated that at least 15 of the 80 facilities in North America known to have participated in MKULTRA were unidentified. The article didn’t seem to cause any other newspapers or magazines to take notice, even though it was backed by more than a year of research and the Rutland Herald had won a Pulitzer Prize for reporting in 2001.

Karen continued her research. In 2009, she began to examine Vermont State Hospital’s death rates, which she found in Empty Beds and Vermont Department of Mental Health biennial reports. She realized “death rates at VSH during the time experiments were being conducted were extremely high and seemed to be way out of proportion.”

That year, she was filmed for four hours by a British film crew for an episode of the Smithsonian Channel show called The Real Story, which aired in 2010. Karen’s part of the show began with the narrator saying, “Psychiatrist Colin Ross has spent more than 15 years researching these unauthorized experiments. He believes that Karen Wetmore was one of thousands of unwitting victims of the CIA’s MKULTRA mind-control program.” For the next five and a half minutes, the narrator, Colin Ross, and Karen told her story. “I just remember thinking ‘What could I possibly have done to be treated like this?’” said Karen about a fragment of memory she had of excruciating pain while straightjacketed in seclusion.

“I feel haunted about the possibility that there are people out there that don’t know that they were experimented on, and that they can’t receive the proper care, and that they may hate themselves like I hated myself,” she said. The Smithsonian Channel was the second time the public had heard anything about CIA experiments in Vermont.

By 2010, Karen had “stopped sending FOIA request and no longer requested the help of elected officials”—probably another reason why the harassment stopped in 2011.

In September 2013, the CIA mailed Karen “Hyde’s more fully declassified MKULTRA Subprojects 8, 10, 63 and 66,” which they’d “refused to make any determination on” when she filed a FOIA request and an appeal in 2003. The documents revealed MKCotton, a previously unknown CIA subproject, and placed Hyde—who died in 1976 and had been VSH’s Director of Research from 1940-1975 and a CIA employee since 1952, and who seemed to Karen to be the CIA’s “most closely guarded” researcher—in Vermont when MKCOTTON, which began as MKULTRA Subproject 63, was operational.

On November 21, 2013, the CIA sent Karen a FOIA-request response that revealed for the first time that VSH research existed and was classified. Karen wrote it was interesting the response “did not state that no records were located” but that records “had been destroyed.”

On April 3, 2014, Manitou Communications, an independent publishing company owned by Colin Ross, published Surviving Evil: CIA Mind Control Experiments in Vermont. In eight chapters and six appendices of evidence, Karen shared her discovery—over decades of therapy, research, and investigation—that the CIA seemed to have done terminal experiments at VSH in conjunction with Vermont College of Medicine for at least two decades and that she was one of the survivors. She published the death rates she’d found and wondered if the numbers hid terminal experiments.

(Karen didn’t directly estimate how many died people at Vermont State Hospital, but from my calculations, based on the death rates from 1952 to 1988 listed in Surviving Evil and Empty Beds, I estimate that around 1255 of the 2789 patients who died at VSH from 1952 to 1972 may have died in unwitting experiments: 11.8% of patients died at VSH per year from 1952 to 1972, while only 5.2% died from 1973 to 1984, and only 1.275% died per year from 1985 to 1988. Taking 5.2% as the VSH death rate minus terminal experiments, I reached my estimate of 1255 or 6.6% of 24,126 patients from 1952-1972, the experimentation period.)

“Numerous published accounts of the CIA drug and mind control program detail CIA plans to conduct ‘terminal experiments,’” wrote Karen. She referenced a 1954 CIA cable that contained a desire for “time, places and bodies for terminal experiments.” Terminal experiments, she pointed out, would be “the one CIA activity that would cause such a massive, coordinated state and federal cover-up,” going beyond the normal cover-up of MKULTRA.

Karen was in her sixties when Surviving Evil was published. She had no explanation for why she survived so many deadly procedures. What was “so disturbing all these years later,” she wrote, was “not knowing the full story” of her past. Her sentiment echoed the Robert F. Kennedy statement from the 1977 Senate hearing that I quoted earlier: “Perhaps most disturbing of all was the fact that the extent of experimentation on human subjects was unknown.”

Surviving Evil revealed a portion of the MKULTRA unknown. How much more remains unknown is itself unknown. In the Senate hearing, Kennedy stated that “no one—no single individual—could be found who remembered the details” despite “persistent inquiries” since 1975, when the public and most of the government learned of MKULTRA, which the CIA claims ended in 1973 but most likely has continued under different names, with greater secrecy. Kennedy didn’t mention the glaring fact that revealing information about a military secret project was punishable by death. As Karen articulated in her book:

CIA briefs Governors, Congressmen and Senators on classified programs, insuring that the official can never speak publicly about the information. The penalty for doing so is treason.

If evil is a form of unfair, one-sided, prolonged, tortuous, extreme pain whose source is hidden to its recipient—something that is epitomized by the terminal experiment that is done on an unwitting nonvolunteer—it is not something that can be destroyed. It is not a person or organization that can be identified and eliminated. It is a cultural phenomenon that any one of us can help minimize over time by detecting, studying, understanding, describing, and exposing it to the masses.

I found Surviving Evil in 2016 while researching MKULTRA for my 2018 book Trip: Psychedelics, Alienation, and Change. I found it by searching “MKULTRA” on Amazon and looking at every result. I ordered it, read it, and began work on this essay.

While working on this essay, in October 2016, I researched the response to Surviving Evil. It had fifteen reviews on Amazon, with all but two rating it five stars. A three-star review said in entirety, “Terrible if true.” Surviving Evil didn’t seem to have been mentioned by any international, national, weekly, local, or college newspaper or magazine.

In May 2014, a month after Surviving Evil was published, Karen had been interviewed by Gnostic Media. In June, a site called Shadowproof published a review of Surviving Evil. In July, Karen was on a radio show called The Power Hour. In 2015, two obscure websites (RenewAmerica and Borne) published reviews of her book; a French TV channel aired an 8 minute 39 second segment on her that was available on YouTube; and Laurie Roth wrote an article titled “Mind Control Experiments on the Mentally Ill—Vermont State Hospital and the CIA” for a site called Sharon Rondeau’s The Post & Mail. In 2016, Surviving Evil did not get any coverage except for its first written review on Goodreads: “Harrowing but absolutely convincing account of a young woman's torture and imprisonment…”

Based on a Google search of “‘karen wetmore’ ‘surviving evil,’” which returned results mostly for Amazon-like websites, selling it in various countries, this was all the attention the media had given the book in its first thirty-one months in the world.

Eight years later, it’s October 2024, and Surviving Evil has 79 reviews on Amazon, with a 4.4 average rating. I posted an earlier draft of this essay on Medium in 2019 and included three paragraphs on Wetmore in my 2021 novel Leave Society, but the Rutland Herald article from 2008 is still the only attention Wetmore has gotten from mainstream newspapers and magazines. A Google search returns the following new coverage—since 2016—for her book:

A 2017 Reddit post titled “Looking for a good nonfiction book regarding MKUltra”; a 2018 conversation between me and my friend Brad Phillips in Autre Magazine; a Heavy Traffic interview (date unknown) with Brad; various interviews/tweets with/by me, including a tweet titled “Some books I'd assign in my journalism school”; a 2018 list of my book recommendations for The Week; a 2021 conversation between me and Brad in Office Magazine; a 2021 conversation between me and Anna Dorn in Granta in 2021; a 2023 article in Gumshoe News; and a 2024 post on a Substack called Hidden Histories.

I marvel at Karen Wetmore's survival instinct and sheer will to keep going in the face of evil forces.

So tragic, thanks for writing it.